A Liar won the Nobel Prize, but that’s Okay

1923 Nobel Prize in Physics Revisited

Over the years, the physical phenomenon we are interested in have become more and more abstruse.

Given the increasingly complex nature of new physics taking place, rarely do we see a theory and its confirmation being separated by short time intervals, let alone being acknowledged and accepted as the mainstream. But astonishingly, this is exactly what happened in the cases of the discovery of the electron and the photoelectric effect, which we, a century later, take for granted. Nonetheless, the journey of acceptance of the same was a hard one.

Any novel idea challenging the champion theories must not only explain the previous observations but also provide enough evidence for justification of its existence as an independent and an updated model of reality. Fortunately, this barrier was overcome quickly, much to the credit of experimentalists like Millikan, without whose contributions, the progress of modern physics would have been significantly delayed. It is interesting to note that it was in 1921, a mere 2 years before the happening of our interest today that Albert Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the law of photoelectric effect.

And it was only in 1923 that the American experimental physicist Robert Andrews Millikan won the Nobel Prize in Physics “for the measurement of the elementary electric charge and for his work on the photoelectric effect”.

Background

Atoms and their existence is a topic of several long-drawn discussions involving not just physics but chemistry and philosophy dating back to the Greeks.

But the first major milestone in scientific probing of this idea must be credited to John Dalton, who in 1804 revolutionised the natural sciences with the postulates of his atomic theory.

So, that is what we will consider our starting point.

Gas Discharge

The 1800s saw a rapid advancement in the development of the atomic theory, which came from studying the electrical discharges.

Glow discharge is a phenomenon that occurs in a glass tube (earliest version being the Geißler tube, named after the physicist Heinrich Geißler who first observed this glow in 1857) containing 2 metal electrodes at either ends with high voltage applied across the two in presence of a gas kept at extremely low pressure. A glow fills the entire tube, just like we see in neon signs.

Gases being a collection of basically unbounded particles bouncing off of each other implied no interaction between the atoms/molecules was at play behind this phenomenon. What this meant was that something novel was happening in the atoms themselves.

Around 1869 to 1875, English physicist William Crookes built on Geissler’s invention and created another discharge tube, now called the Crookes or Crookes-Hittorf tube, which was able to maintain pressure several magnitudes lower than that possible with Geißler tubes.

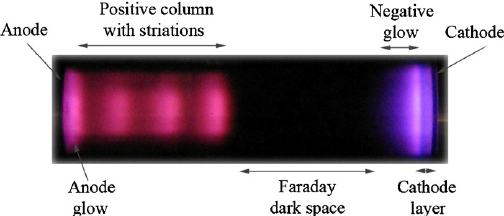

(Source : Lisovskiy, Valeriy & Koval, V & Artushenko, E & Yegorenkov, V. (2012). Validating the Goldstein–Wehner law for the stratified positive column of dc discharge in an undergraduate laboratory. European Journal of Physics. 33. 1537-1545. 10.1088/0143-0807/33/6/1537)

From the image it is clear that there is a noticable dark space in front of the cathode, which was first observed by Faraday and hence appropriately named the ‘Faraday Dark Space’, though it is also sometimes referred to as the ‘Crookes Dark Space’ due to the it being observed in just Crookes tubes and not in Geißler tubes.

The length of this dark space was dependent on the pressure of gas inside the discharge tube. As the pressure is decreased, the length continues to increase until it reaches the anode, at which point the glass present behind the anode begins to glow.

This phenomenon was first observed in 1859 by Julius Plücker and Johann Wilhelm Hittorf, who postulated the existence of rays which travelled from cathode to anode and caused the fluorescence of anode glass. These were named cathode rays (Kathodenstrahlen) by Eugen Goldstein in 1876.

Besides discovery of cathode rays (which we now know are composed of some subatomic particle), Crookes tube was also used by the German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen for his discovery of X-rays in 1895.

Thompson’s Discovery and Previous Attempts

In 1897, the English physicist J. J. Thomson published a paper named “Cathode Rays,” in the Philosophical Magazine.

In this paper he showed that cathode rays are composed of an unknown negatively charged ‘corpuscles’, which were later named the electron. With a mass about 1/1837 times smaller than that of a hydrogen atom, these cathode rays were independent of nature of the gas used in the discharge tube. Since these particles weighed much lighter than even the lightest of the atoms, this ‘corpuscle’ had to be a new kind of particle - a subatomic particle.

In the early 1900s, existence of subatomic particles was disputed. As Thomson had already discovered the charge/mass ratio of the electron, either of these two values needed to be discovered so that the other could be calculated easily.

Back in 1874 an approximate value of this charge was arrived at by using laws of electrolysis, which came surprisingly close to the value subsequently determined by Millikan - 2/3 of it to be precise. Using more sophisticated methods, attempts were made by Thomson and others, who tried to measure the fundamental electric charge using clouds of charged water droplets by observing how fast they fell under the influence of gravity and an electric field. The method did give a crude estimate of the electron’s charge.

However, the results were far from conclusive and disagreements, if not full-fledged controversies were commonplace.

Oil Drop Experiment

Principle

Millikan along with his student L. Begeman began his investigations of the electronic charge in 1907.

They did this with a view of improving the method of H. A. Wilson, a colleague of J. J. Thomson at Cambridge University, who had performed one of the earliest measurements of the electron’s charge.

His method consisted of ionizing the air in a fog chamber and condensing a cloud on the ions by means of a sudden expansion. To determine the charge, the rate of fall of the cloud was to be measured in the following 2 conditions

- Under gravity alone

- When a vertical electric field was super-posed on gravity

The force of viscosity on a small sphere moving through a viscous fluid is given by Stokes’ Law. Using this law the mass of the droplets constituting the cloud from the velocity of their descent under gravity can be obtained. Moreover, the velocity in the electric field gave information about the ratio of the electric to the gravitational forces which could further be used to find the ionic charge.

Challenges

Millikan set out to improve on the findings of Wilson and realized that trying to determine the charge on individual droplets works better than measuring charge on whole clouds of water.

So in 1909, he began the experiments, but soon found that droplets of water evaporated too quickly for accurate measurement. He asked his graduate student, Harvey Fletcher, to figure out how to do the experiment using some substance that evaporated more slowly. Fletcher quickly found that he could use droplets of oil, produced with a simple perfume atomizer.

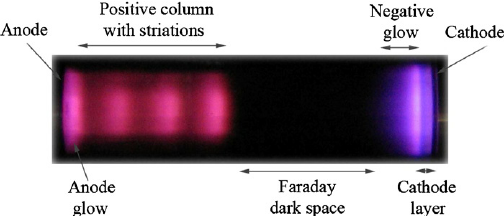

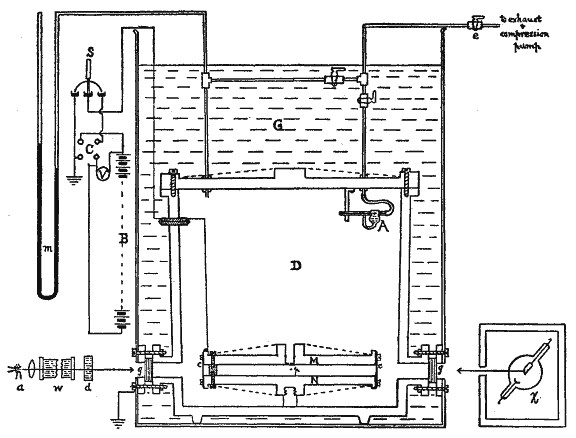

Diagram of Millikan’s apparatus from his Physical Review paper

In the final form of the experiment a cloud of oil drops is produced by an atomizer. The drops are allowed to fall under gravity through a hole in a plate which constitutes the upper member of an accurately machined pair of plates between which an accurately measured electric field can be applied. A single droplet is selected for observation through a low-power microscope and its rate of fall under gravity is observed. If the viscosity of the air is known, the size and, hence, the weight of the drop is determined. The electric field is now applied in such a direction as to counteract gravity and a new rate of fall or rise is determined.

If, for example, the electric field is adjusted to hold the droplet at rest, the upward force must equal the weight, and the charge is at once determined.

Work on Photoelectric Effect

Though his work on the determination of e

is most well recognised, Millikan had also verified Einstein’s 1905 quantum theory of the photoelectric effect.

Milikan thus achieved an unparalleled feat which established the atomic or quantum nature of light. Einstein had proposed a linear relationship between the maximum energy of electrons ejected from a surface, and the frequency of the incident light on the basis of Planck’s quantum theory assuming that light actually consisted of discrete energy packets called ‘quantum’ (plural ‘quanta’) of light. The slope of this line was nothing but the Planck’s constant, introduced 5 years earlier by Planck. In 1915, Millikan experimentally verified Einstein’s photoelectric equation, and made the first direct photoelectric determination of this Planck’s constant h.

So, in the pursuit of curiosity, Millikan paved the way for not one, but 2 Nobel Prizes in Physics - one for himself and other for Einstein and ended up becoming only the second American to receive the honor.

Controversies

In any experimental investigation, the data collected is not devoid of errors.

Thus experimentalists have considerable liberty is deciding which data is to be neglected or disregarded, albeit the decision is guided by some statistical rules. This becomes especially important in cases of tests of cutting edge theories and other ground breaking discoveries as their confirmation depends quite a lot on both the accuracy and the precision of the measurement.

Keeping in mind the substantial skepticism towards the sub-atomic particles, Millikan’s experimental findings would have been subjected to serious scrutiny, which Millikan was aware of as well. This notion played on the minds of the scientific community, owing to which Millikan was involved in a data selection controversy with Felix Ehrenhaft over the quantisation of charge.

This continued well after Millikan had won the Nobel Prize

Case Study

In the year 2000, Theodore Goldfarb and Michael Pritchard of the Center for the Study of Ethics in Society at Western Michigan University published an instruction guide named Ethics in the Science Classroom, which included a case study of Millikan’s work on the oil-drop experiment. Given below is an extract from their publication.

An examination of Millikan’s own papers and notebooks reveals that he picked and chose among his drops. That is, he exercised discrimination with respect to which drops he would include in published accounts of the value of e, leaving many out. Sometimes he mentioned this fact, and sometimes he did not. Of particular concern is the fact that in his 1913 paper, presenting the most complete account of his measurements of the charge on the electron, Millikan states “It is to be remarked that this is not a selected group of drops but represents all of the drops experimented upon during 60 consecutive days.” However, Millikan’s notebook shows that of 189 observations during the period in question, only 140 are presented in the paper.

Millikan’s results were contested by Felix Ehrenhaft, of the University of Vienna, who claimed to have found “subelectrons.” Moreover, Ehrenhaft claimed that his finding was in fact confirmed by some of Millikan’s own data – droplets that Millikan had mentioned but discounted in his published writings. The result was a decades-long controversy, the “Battle over the Electron,” over whether or not there existed subelectrons, or electrons with charges of different values. This controversy makes an excellent case study because we are fortunate, thanks to Millikan’s notebooks, to be able to see very specifically which drops he included and which he did not.

Professor Allan Franklin, a science historian at the the University of Colorado Boulder, analysed, in detail, Millikan’s data sheets from California Institute of Technology in his paper on his Oil Drop Experiment and came to the conclusion that without doubt, Millikan was guilty of some amount of data selection.

He writes, ‘Millikan also engaged in selectivity in both the data he used and in his analysis procedure. In presenting his results in 1913 Millikan stated that the 58 drops underdiscussion had provided his entire set of data.

“It is to be remarked, too, that this is nota selected group of drops but represents all of the drops experimented upon during 60 consecutive days, during which time the apparatus was taken down several times andset up anew” This is not correct.

Millikan took data from October 28, 1911 to April 16, 1912. My own count of the number of drops experimented on during thisperiod is 175. Even if one were willing to count only those observations made after February 13, 1912, the date of the first observation Millikan published, there are 49 excluded drops. We might suspect that Millikan selectively analyzed his data to support his preconceptions.’

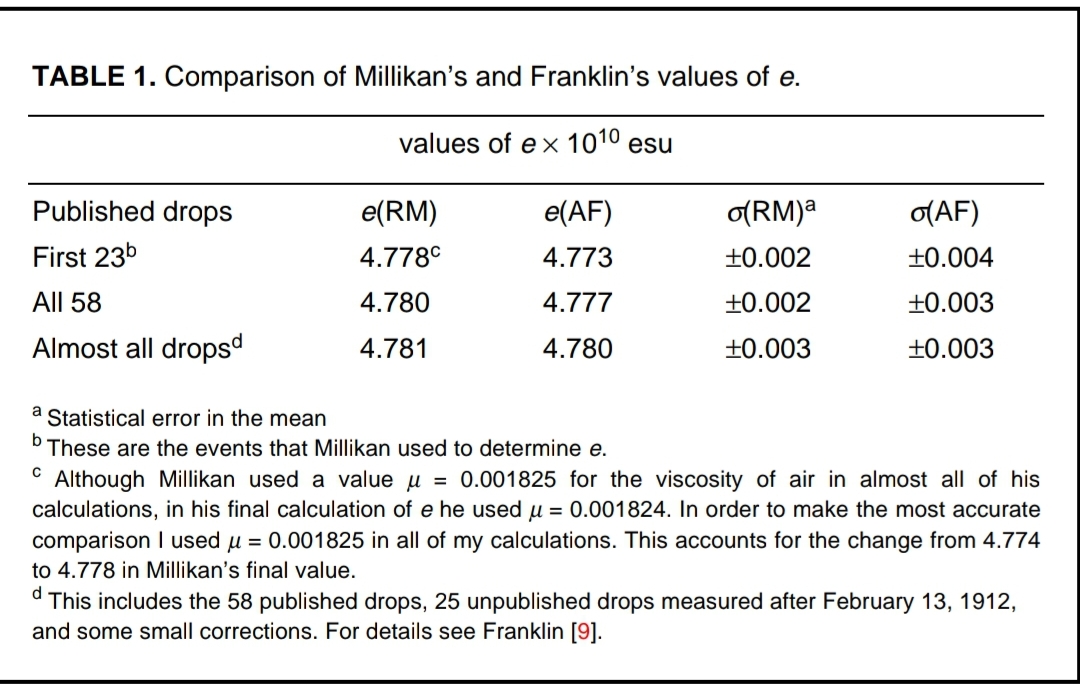

Table from Allan Franklin’s Paper

But Franklin also notes that, ‘The effect of Millikan’s selectivity was quite small and is shown in Table 1. This includes Millikan’s results along with my own recalculation of Millikan’s data. As we can see the effects of Millikan’s selectivity are quite small.’

Significance

In words of Gullstrand, ‘Millikan’s aim was to prove that electricity really has the atomic structure, which, on the base of theoretical evidence, it was supposed to have’.

Not only did Millikan experimentally prove the same, but he also made the discovery that all electrons carry the same amount of negative charge. Infact, Millikan considered the experiment to be such a direct and irrefutable demonstration of the atomicity of electric charge that he wrote in his autobiography that “he who has seen that experiment, and hundreds of observers have observed it, [has] in effect SEEN the electron.”

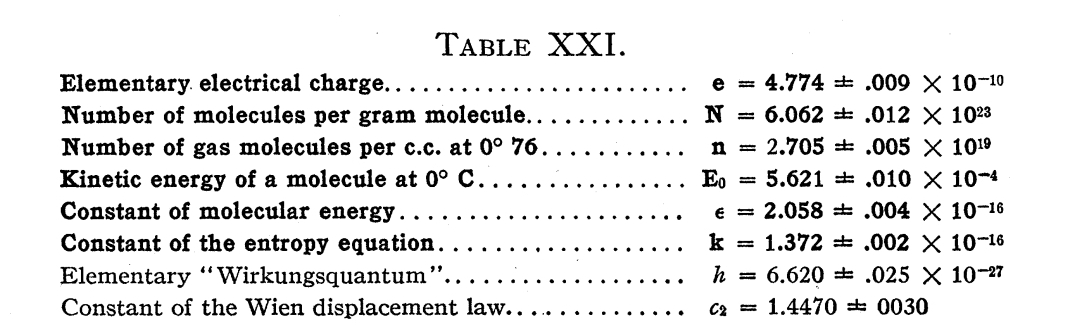

At the time, no determination of charge e by any other method existed which did not involve an uncertainty at least 15 times as great as that represented in Millikan’s measurements. The calculation of elementary charge by Millikan enabled us to calculate, with unmatched precision, a large number of the most important physical constants.

Physical constants measured by Millikan

Although the investigation had been repeated by several other researchers, the accuracy of Millikan’s results was never equaled.

References

- Robert Andrews Millikan (1868—1953) : A Biographical Memoir by L.A. Du Bridge and Paul A. Epstein

- On the Elementary Electrical Charge and the Avogadro Constant by R.A. Mullikan (Phys. Rev. 2, 109 – Published 1 August 1913)

- Presentation Speech by Professor A. Gullstrand, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, on December 10, 1923

- The Millikan Case - Discrimination Versus Manipulation of Data by Michael Pritchard and Theodore Goldfarb

- Millikan’s Oil-Drop Experiments by Allan Franklin (The Chemical Educator - Published April 1997)

- https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200608/history.cfm

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cathode_ray

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oil_drop_experiment